In my autoethnographic account: ‘FEMININITY IN JAPANESE ANIME’, I explored how my initial ideas of femininity, including how they are visually portrayed, were challenged. This occurred through my viewing of various anime and Studio Ghibli films.

Throughout this account, I used epiphanies to present to my readers just how different Hayao Miyazaki’s portrayal of females were compared to animations that I was previously used to e.g. Disney and the damsel in distress stereotype. These epiphanies impacted on and helped to further shape my understanding of femininity in anime.

I used Ellis et al’s methodology of “storytelling” and “showing” in an attempt to familiarise my audience with the characters of whom I was talking about, and by doing so, ‘bring “readers into the scene” – particularly into thoughts, emotions, and actions.‘(Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011). I also did this as a way of informing my readers, who may not be familiar with anime, of the way females can be portrayed. I wanted them to somehow experience what I was experiencing for the first time.

My first epiphany was when I was a child watching a lot of different cartoons and I came across Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away on TV. I distinctly remembered the difference in animation style. However, it was my exposure to the different styles of animation (Japanese and Western) that made me aware of how different the female leads were, specifically in Miyazaki’s Ghibli films.

As stated in my previous post, reflecting on this has made me curious as to how the notion of femininity in Japanese anime relate to past and current Japanese art.

Stockins explores these notions in her 2009 thesis ‘The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney‘. In order to strengthen my understanding of anime and its portrayal of femininity I will continue to refer to Stockin’s thesis, thus providing a layered account (Ellis et al., 2011) of my experience with anime culture so far.

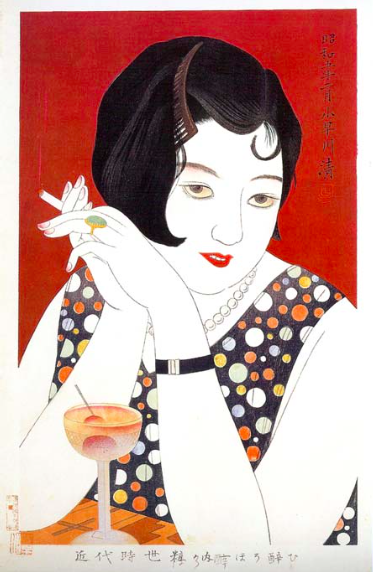

During the Taisho Era in Japan, people began to travel more, resulting in exposure to ‘aspects of Western culture.’ (Stockins 2009, p. 14). This exposure began to have an impact on Japanese culture and consequently resulted in a new attire for the ‘modern girl or Moga‘ (p.13). This attire was more revealing than the traditional Kimono and hairstyles became more laid back and relaxed. As a result, artists commonly sexualised Moga’s in their works.

The females gaze is direct and her demeanor suggest that she is trying to seduce the subject of her gaze.

Contrastingly, this work depicts a Geisha dressed in the traditional Kimono. It exudes conventional Japanese femininity with the lack of eye contact and waif like figure to appear graceful and fragile. (Stockins 2009, p. 69)

These depictions of femininity from the early 20th century seem quite far removed from those depicted in Studio Ghibli films of the late 20th to early 21st century. The romance, intrigue and allure associated with the women in these artworks remind me of the concept behind Shoujo (MadameAce, 2012) anime [animation]/manga [comics] for girls.

In Shoujo, it is common for the character’s eyes and head to be exaggerated, with the purpose of creating an ‘infant-like.’ (Stockins 2009, p. 69) appearance.

Despite the illustrations of these artworks and Shoujo being quite different, they both seem to be based around the concept romance and attracting a mate through physical appearance.

‘The Shoujo commonly depicted as a young school girl character that embodied purity and Kawaii (cute) culture became Japan’s new sex symbol…‘ (Stockins 2009, p. 25)

The allure and point of intrigue with females in Studio Ghibli films is not based on how they appear, but what they do. I did not realise how different anime could be in terms of depicting femininity. Then again, I don’t know why I should be surprised; people have their preferences and considering the umbrella market of anime, there must be a plenitude of different fan bases.

In Spirited Away, Miyazaki states how he wanted to deter from the concept of “crushes and romance” (‘Interview: Miyazaki on Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi‘, 2001) that were abundant in Shoujo.

‘Girls are usually naive and wide eyed, rushing stupidly into trouble only for the brave hero to pull them out of it.’ (Olowu 2013, p. 1)

It seems to me that one of the reasons behind the success of Studio Ghibli films directed by Miyazaki is due to the deviation from anime’s conventional gender roles and the unlikely heroes found within the lead female characters:

- Spirited Away: A 10 year old girl, Chihiro, saves her parents and friend Haku.

- Howls Moving Castle: 19 year old Sophie is cursed and turned into a 90 year old woman. Despite all the odds against her she saves Howl and his moving castle.

- Princess Mononoke: multitude of dominating female characters.

This brings me to the portrayal of femininity in cosplay and how anime influences this.

Within my cultural framework, there is not a huge focus on cartoons, specifically anime. In fact, I am deprived of anime in my cultural framework. In saying this, I know there are many people from my culture who can relate to this.

Why?

It seems that anime has a nation-wide appeal regardless of age, whereas in Western society, there is a belief that cartoons are typically associated with childhood.

If this is the case then why is cosplay so popular in Australia? Australia is without a doubt a multi-cultural land, but how could something so far removed from our everyday culture attract the kind of fan base that anime does?

When I attend Comic Con this year, I will be intrigued to see how anime has influenced the dress of the conventions attendees.

Reblogged this on Digital Asia.

LikeLike

Femininity is a great idea to focus on, as the way in which females are represented is so diverse depending on the culture. It’s awesome that you’re exploring the notion of femininity in relation to Japanese anime from past and current Japanese art, that way you can contrast between the two and reveal the differences, if there is any. I like how you referred to Kobayakawa’s ‘gaze’ during my art theory studies, I’ve learnt a lot about the concept of the ‘gaze’ in relation to how an audience views the people presented. The concept of the gaze became popular with the rise of postmodern philosophy and social theory, this article explains more about it and might be of use to you http://www.artandpopularculture.com/Gaze

I also found this article that contrasts masculinity vs femininity in Japanese culture which could be a useful, unique way to look at your project http://www.handa-links.com/masculinity-femininity-japanese.asp

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome, thanks so much for the additional sources! In highschool I remember studying the ‘gaze’ and the significance of it, especially when considering the works context. I love analysing art works so I hope to continue that aspect on in my research.

LikeLike

This is a brilliant topic to study and I really enjoyed your analysis!

In your detailed analysis of feminism in Japanese texts, you’ve focused a lot on allure as a result of the way females’ bodies are positioned and the direction of their gaze. You’ve mentioned the typical Disney ‘damsel in distress’ character as your own ‘experience’, but I wonder what might happen if you took this one step further and considered the postures and gazes of women (and perhaps men also) in your local area? This source (http://www.study-body-language.com/Posture-and-body-language.html#sthash.L40jgLuq.dpbs) discusses how “non-verbal communication” like posture often plays a huge role in social interaction – whether it’s intentional or not. This could be an avenue to further bring your “readers into the scene”, an idea you’ve cleverly pulled from the Ellis et. al reading. Perhaps a localised understanding of body language could help both you and your audience to understand the femininity in Japan even more than you do now!

Claire

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, thank you for your comment!

Thats a really interesting approach I hadn’t even considered, especially to see if such a thing like posture differs between various social/cultural groups. Ill have to suss it out now

LikeLiked by 1 person